There’s Something About Dry Stout

Yes, there’s something about Dry Stout – something tall, dark, and wholesome.

“The Dry Irish Stout is a counterintuitive brew,” writes beer journalist Joshua M. Bernstein in his book The Complete Beer Course. “Though it’s the color of La Brea tar pits, dry stout is sneakily light-bodied, offering an appealing bitterness (courtesy of roasted barley), coffee-like nuances, and, if dispensed using nitrogen, a nice creaminess like frosting on a birthday cake.”

Undeniably refreshing, Dry Stout is one of the world’s most popular beer styles, perhaps second only to the light lager. Here in the US, it is the official non-green beer of St. Patrick’s Day; in Ireland and elsewhere Dry Stout is revered all year.

Dry Stout Profile

Bittersweet but balanced, a standard Dry Stout pours deep brown to jet black in color (25-40 SRM). Modern examples are typically served on nitro or low CO2, producing a long-lasting creamy crown ranging from tan to brown. [Note: Bottled products do not produce this effect.]

The BJCP describes the Dry Stout style as remarkably smooth, noting its high hop bitterness and characteristic reliance on dark grains. This author agrees; drinking more than a few jars is easy, thanks to its friendly ABV that ranges from 3.8-5.0%.

Oh, Wanna Whole Lotta Stout

Travel the Irish tavern circuit and you’ll notice that regional differences exist among the Dry Stouts available on draught. Brewers around Dublin tend to use more roasted barley – up to 10% of the total grist – which leads to increased bitterness and a drier finish. Their counterparts from Cork, however, prefer a slightly malty-sweet finish that comes from swapping out some of that roasted barley for a bit more chocolate and specialty malts.

Whatever your preference, coffee aromas ought to dominate the nose, with notes of dark chocolate, cocoa, and roasted grain layered in there. A medium body with a creamy character is appropriate, as are flavors of coffee, bittersweet chocolate, mild dark fruits, and earthy hops. Are you salivating yet?

Compare these bitter Irish beers to Sweet Stouts or Milk Stouts from England, where the addition of lactose creates the sensation that you’re sipping on sweetened espresso.

Or consider the Imperial Stout – the strongest, darkest, and most intense stout of all. Rich, deep, and complex, Imperial Stouts strike a balance between high bitterness, strong malty sweetness, and big ABVs ranging from 8-12%. Some brewers have been known to barrel age these bad boys in bourbon, rum, and other intoxicating spirits.

Commercial Examples

The most popular example of the Dry Stout style is Guinness Draught Stout, poured daily in pubs and dives from Dublin to Dubuque to Dubai. When served on nitrogen, this O.G. stout swirls like a storm before slowly settling into the perfect pint. At 4.2% ABV, it is suitable for quick pick-me-ups as well as long silly evenings with your best drinking buddies. Modern drinkers who attempt to “Split the G” may not be aware, but when they take that first big gulp of Guinness, they’re putting a new twist on a drinking tradition that goes back over 265 years. Other Dry Stouts we know and love include:

- Pfriem Dry Stout

- Murphy’s Irish Stout

- Beamish Irish Stout

- O’Hara’s Irish Stout

- Left Hand Dry Irish Stout Nitro

- Russian River O.V.L.

- Three Floyds Black Sun Stout

- Brooklyn Dry Stout

A Pint of History: The Dark Side of Beer

“If it were not for the mass-produced, delicious ubiquity of Guinness,” Bernstein writes, “millions of beer drinkers most likely would not take their first baby steps away from light, crisp lagers and dabble in the dark side of beer.”

The man makes a salient point. But before Guinness Draught became the gateway to black beer, there was Porter, specifically the London-style Porter, which first appeared in the early 1700s. This style got its name, according to legend, from the folks who drank it most – thirsty working-class men who hauled heavy loads and freight for their daily pay.

Over the decades, Porter grew in popularity and was exported far and wide. Stronger “stouter” versions of Porter sprang up as English and Irish brewers alike introduced creamier, fuller-bodied interpretations. By the late 1800s, Irish Stout had become its own distinct thing, characterized by darker malts and roasted barley.

Ready to Brew? RahrBSG Manager of Training and Technical Support Ashton Lewis offers up his tried-and-true recipe — Riffin’ on a Classic Dry Stout.

Ashton has been brewing this stout for years, but he’s offered a few modern twists this time around. Of particular note, he’s replaced a portion of roasted barley with Simpsons Export Pale Brown for a subtle dark cacao layer of complexity. He’s also using an all new Chit Malt from Gambrinus.

OG: 10.00 P

FG: 2.25 P

Est. ABV: 4.06%

Mash L:G Ratio: 2.60

MALTS

Malting Company of Ireland Irish Stout Malt: 77%

Simpsons Roasted Barley: 9.0%

Simpsons Export Pale Brown Malt: 4.0%

NEW! Gambrinus Chit Malt: 10.0%

HOPS

German Hallertauer Magnum: 60 Minutes / 35 IBU

MASH

Rest 1: 65° C for 45 minutes

Rest 2: 70° C for 10 minutes

Rest 3: 76° C for 2 minutes

FERMENTING YEAST

Fermentis SafAle™ S-04: 0.65 g/L

NOTES ON SERVING

Ashton suggests a carbonation level in the range of 2.4-2.5, or going with mixed gas and a stout faucet, which is his preferred method.

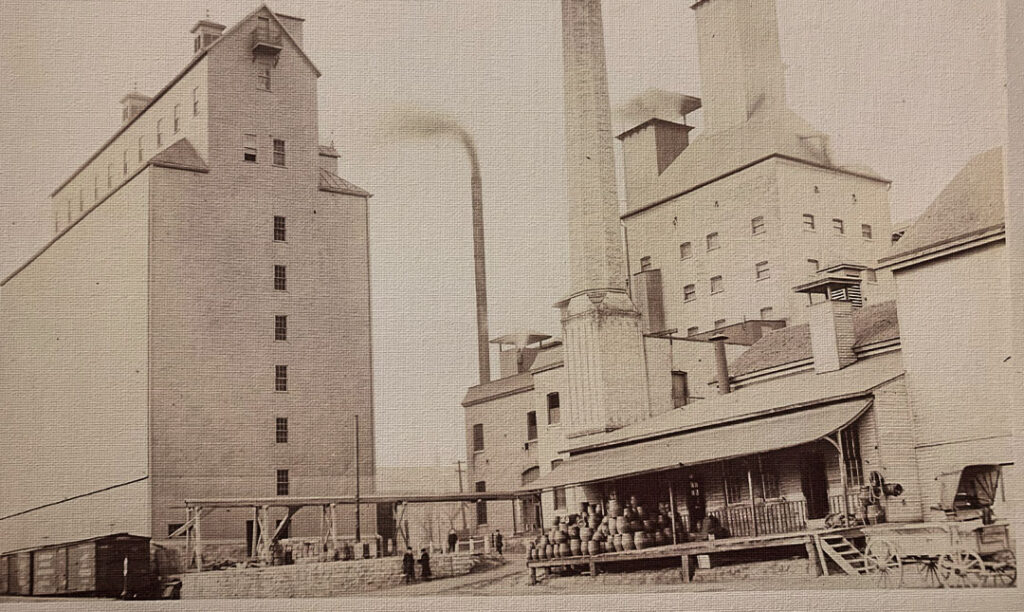

More About The Malting Company of Ireland

The Malting Company of Ireland goes back to 1858, tracing its heritage to the old floor maltings of Beamish & Crawford in the heart of Cork. Over 167 years later, MCI operates a state-of-the-art facility in County Cork, where they produce the finest Irish malt for Ireland’s most renowned brewers and distillers.

Their mild-flavored Irish Stout Malt was developed with ease of conversion in the mash in mind, making it highly versatile for various beer styles. This malt provides high extract and enzymatic strength, and it is specially designed for use with raw adjuncts. No blarney, it is the ideal foundation for the Dry Stout of your dreams.

Go on, get started. The yeast is hungry.

Beamish-ish Dry Irish Stout Brew Day at Gambit Brewing

Resources